The Proclamation of Independence, as read out on the steps of the GPO by Padraig Pearse during the Easter Rising of 1916, is arguably the most seminal and instantly recognisable text ever produced in the history of Ireland, and its meaning is fascinating. In just 487 words, it encapsulates the spirit of the seismic change proposed by the rebels as they announced the Irish Republic would henceforth function as an independent sovereign state.

Proclamation of Independence’s Call to Arms

The text of the Proclamation of Independence is a rousing call to arms and freely mixes fact with aspiration and idealism. It draws on references to mythology and history as it outlines the vaulting ambitions of its authors. For its time, it encompassed a notably progressive point of view, pushing for a new political and landscape for Ireland based on equality across the spectrum. All seven men were no doubt fully aware that when they signed their names below this extraordinary proclamation, they were also metaphorically signing their own death warrants. Deconstructing the meaning of the Proclamation can help to shed light on the passionate convictions that drove them to such extreme measures.

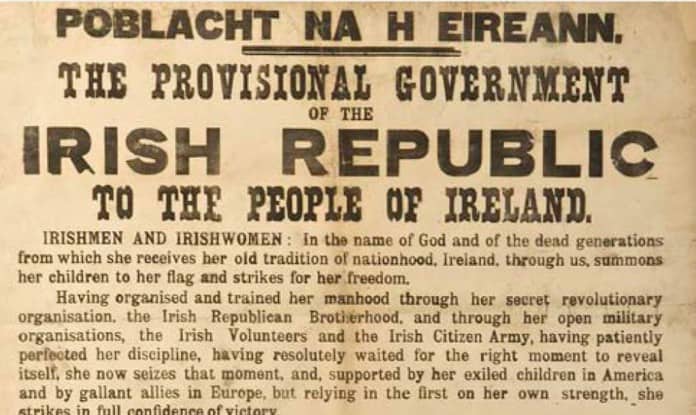

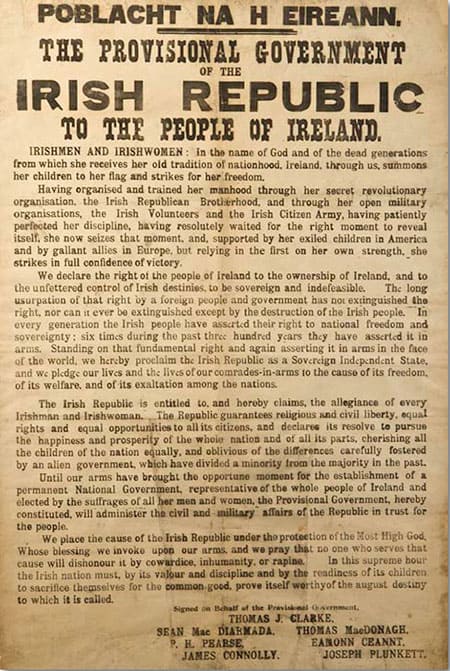

The first words in the proclamation – POBLACHT NA H EIREANN – are the only Irish words used in the document. ‘Poblacht’ has over time come to mean ‘democracy’, though it was not used in this way in 1916. The phrase ‘the Provisional Government of the Irish to the people of Ireland’ signifies that the Proclamation is directed at the people as one entity, as the true heirs of the land. The reference to Irish men and Irish women is extremely enlightened for the time, as it hails women as equal to men under the banner of the new Irish Republic. For context it should be remembered that this was the era of the suffragettes in the UK and was a time when women across the world were subjugated as a matter of course. The phrase ‘in the name of God’ respects the highly religious nature of the country at the time and was designed to appeal to all God-fearing citizens. The ‘dead generations’ is a reference to those who had already lost their lives fighting for independence, invoking the memory of their sacrifice to inspire a new generation. To ‘strike for her freedom’ implies that violence will be a necessary tactic to achieve an independent state.

Time for a Revolution

The main implication of the next paragraph is that this is a revolution that is perfectly timed and that is the culmination of a well-organised and coordinated effort across the IRB, the ICA and the IVF – essentially how the planets were perfectly aligned to seize the day. The ‘Exiled Children’ are those who fled abroad during and after the Great Famine, those who left as a rejection of British rule and the members of the organisation Clan Na nGael. The ‘gallant allies in Europe’ refers to German support, although this is not explicitly stated. It was this phrase that pushed the rebellion over a line in the minds of the British, elevating it and ultimately leading to the death sentences for the seven men. The assertion that the Irish nation, in ‘relying on her own strengths, strikes in full confidence of victory’ was baseless. From Easter Monday the leaders were entirely aware that their rebellion would be put down, as they had neither enough men nor enough weapons to defeat the British forces.

The third paragraph outlines the rebels’ vision for a new and improved country and justifies the measures taken to achieve it. The ‘right of the people to ownership’ is a pivotal sentence, as the issue of land ownership had been a sore point for many since as far back as the 17th century. The ‘unfettered control of Irish destinies’ makes it clear that nothing less that total independence would be deemed acceptable. The leaders of the rebellion legitimised their use of violence by reasoning that they were the latest in a succession of radicals who ‘six times during the past 300 years’ had declared that the use of arms was pivotal to achieving independence from Britain, with the implication being that the Rising was simply the latest manifestation of what was already a firmly established tradition of nationalism.

The first sentence of the fourth paragraph personifies the Irish Republic, who speaks to the people, claiming the loyalty of every citizen. The framework of the new Republic is set out clearly – guaranteeing civil and religious liberties for all and offering equal opportunities and rights to every citizen. This newly declared Republic would rise above political and religious tensions and the rules of an ‘alien government’, and every Irish man and women would play their part in the new utopia – a pluralistic and inclusive nation. The signatories offered these progressive ideals to underline their pure intentions, however outlandish they may have appeared to the majority of people at that time the Proclamation was written.

The fifth paragraph of the Proclamation of Independence starts, ‘Until our arms have brought the opportune moment’ – that is, violent means are necessary to order to institute a ‘permanent National Government’ that would be fully representative. The meaning here is that the signatories envisage an inclusive government that would serve the people of Ireland and act in their collective best interests.

A Sacrifice for the Greater Good

The final paragraph of the proclamation of Independence puts the success of the rebellion in the hands of the ‘Most High God’, meaning that the seven believed that their planned insurrection fell within acceptable moral and religious boundaries. The reference to ‘sacrifice’ implies that the rebellion is all part of the greater good, and that loss of life is worthwhile if a free Ireland is the result. It is strongly implied that the Rising was not simply politically motivated, but that it was the first step on the way to a seismic change both socially and economically. It painted an idealistic picture of an independent Irish state that would care about all its citizens equally, a socialist concept that was close to the heart of Connolly in particular. Its innate optimism fell into stark relief following the unsuccessful Rising and the death of its main proponents. Over the following years, the energy of the nation was to be almost wholly directed towards the fight for political change, while the issues of economic, social and civil reform, so central to the stated aims of the Proclamation, faded into the background.