When the First World War broke out over a century ago, it soon became clear that it would be necessary to build a number of camps to house all of the German prisoners of war that had been captured. One such camp was the Frongoch Internment Camp in the Welsh hamlet of the same name near Bala, with the first group of prisoners arriving in their temporary new home early on in 1915. This was the site at which the 1916 Rising centenary (also referred to as the Easter Rising centenary) will be marked and where the legendary figure Michael Collins, who would play such a key role in the coming revolution, first came to prominence.

Before the war, the Frongoch Internment Camp was a whisky distillery, which it was said had been founded in the area because the water running in the nearby river was unusually pure. Pure water or not, the business went bankrupt and the buildings that housed it had lain unused for around five years before the arrival of the first German prisoners in 1915. However, events soon conspired to result in the first wave of Germans being replaced in the camp in June 1916 with around 1800 of the Irish rebels, including Michael Collins, who had been involved in the Easter Rising and imprisoned without trial, initially in England. The 1916 Rising centenary (or Easter rising centenary) is set to be a landmark event in this small hamlet, and back in 1916 was actually referred to as ‘Ollscoil na Réabhlóide’, which translates as the ‘University of Revolution’. This reflects the fact that the camp quickly became a hub where the many interned members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (soon to become the Irish Republican Army) started to organise their next moves in their bid to gain independence for Ireland.

The Irishmen were bestowed with the title of prisoners of war and had access to limited facilities. One of these was the organisation of classes in and the promotion of the Gaelic language within the camp. The prisoners were also taught crafts and reading as well as, perhaps surprisingly, military discipline and organisational skills. It can certainly be argued that it was during this time of incarceration that the first seeds of the Irish War of Independence and the eventual establishment of a new Irish state were sown.

In the aftermath of the Easter Rising, many parts of Dublin had been all but destroyed, and the British Empire had put down the rebellion and crushed the rebels’ hope for a new republic in less than a week. Despite this, it was only five and a half years later that the Irish Republican movement did succeed in taking control of the majority of their country from one of the most powerful forces anywhere in the world – the mighty British Empire. It does seem somewhat ironic that the British opted to incarcerate a group of fervent and highly dedicated Irish nationalists together in one place where they were allowed to mix freely, discuss tactics and plan in detail their next moves.

There are quite a number of sources from the time that illustrate day-to-day life in the camp. Several prisoners kept diaries, the most detailed of which are those by Joe Stanley (who was tasked with printing the daily bulletins during the rebellion) and Seamus O’Maoileoin. Both men make frequent references to the emerging dissident voice of Michael Collins (who, interestingly, was actually taught Welsh by local man Johnny Roberts).

Through the words of these men, life in camp is brought to life. We learn how the prisoners struggled to be given the status of prisoner of war and how they adeptly coordinated a propaganda machine to win sympathy and pour shame upon the British government. We also see the early stages of the hunger strikes that were carried out in Frongoch in one of the first recorded episodes of this type of physical protest.

Conditions in the camp could be very harsh. The buildings were old and in a poor state of repair and alternated between being absolutely freezing at night and oppressively hot during daylight hours. In addition, large numbers of rats roamed freely around the compound.

Unusually, the camp was in effect run by those who were imprisoned there, largely because so many British soldiers were busy fighting in World War One. The local population were well aware who their new neighbours were, and many locals worked at the camp, both in the barracks and kitchens, where they often came into contact with the rebels.

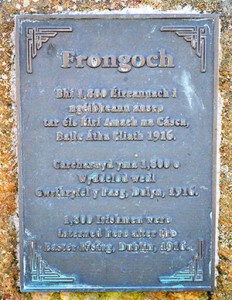

Today the site is unrecognisable from the accounts of the time, although a plaque was unveiled nearby in 2002 by an Irish society based in Liverpool that explains the importance of the location in Irish, Welsh and English. A primary school now stands where the south camp once stood. Other than that, the only other evidence that the camp was once situated in Frongoch is the eerie, long abandoned railway station that is located in the tiny hamlet itself. You can still see the station canopy, signal box and platform, all of which seem strangely well preserved.

Many of the locals still feel a strong connection to past events and are aware of the significance of the plans that were made at the camp, which many feel was the location at which the War of Independence was won, long before the actual fighting began.

The camp closed its doors in December 1916, and because there are so few indications that it ever existed, even many local people were unaware of the part their village played in Irish history until fairly recently.

While a small ceremony takes place every year on Easter Monday by the plaque, the villagers now plan to mark the 1916 Rising centenary (or Easter Rising centenary) with a week-long series of various commemorative events, including a parade, erecting flagpoles flying both the Irish and the Welsh flags, a wreath-laying ceremony and a GAA match. There will also be some panels created that explain in detail exactly what once stood on the site of the Frongoch Internment Camp and about some of the key people who were imprisoned there as a result of the revolution, including Michael Collins – probably the most famous name connected with the planning and execution of coming events.

Locals are keen to recognise both the people who worked at the Frongoch Internment Camp by celebrating the 1916 Rising centenary/Easter Rising centenary (many of whom have descendants who still live in Frongoch) and of course the rebels figures such as Michael Collins who were imprisoned there and whose future revolution, planned in the camp, was to alter history so significantly.