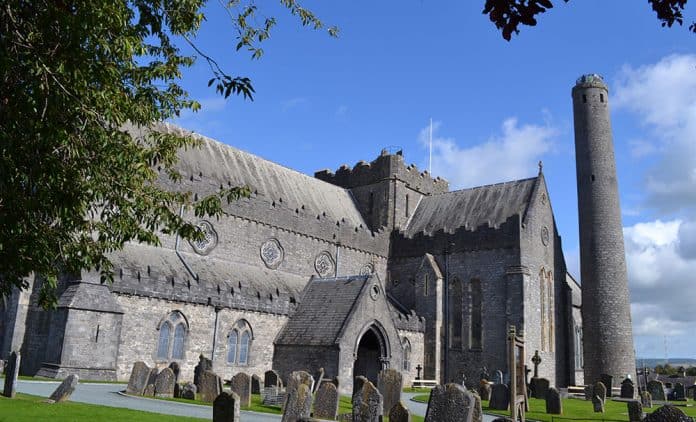

St. Canice’s Cathedral was constructed during the early thirteenth century on a site that had long been regarded as sacred. The monastery that once stood there gives the wonderful medieval city of Kilkenny its name – ‘Cill Choinneach’ in the Gaelic translates as the ‘Church of Canice’. The cathedral is the second largest in Ireland: only St Patrick’s in Dublin is bigger. St Canice’s Cathedral is a priceless piece of Irish heritage, packed with innumerable pieces of invaluable evidence that give an insight into the tumultuous centuries it has witnessed. It’s closely associated with Bishop Legrede and Dame Alice Kyteler, and there is a wealth of fascinating history to uncover during a visit to this atmospheric place and the Round Tower situated close by.

Next to St. Canice’s Cathedral there is a superb example of a ninth-century Round Tower, one of the very few that visitors are still able to climb. The tower is the oldest structure (still standing) in Kilkenny City, and the views from the top are simply spectacular. This is the landscape that formed the background to the witchcraft accusations levelled at Dame Alice Kyteler by Bishop Legrede.

Legend of the Two Saints

The story goes that St Canice and St Columba were dear friends. One dark night, the ship St Columba was travelling on sailed into a terrible storm, and the lives of all on board hung in the balance. St Columba’s fellow monks implored him to pray for them, whereupon he serenely replied that there was no need as Canice would pray for them and all would be well. Meanwhile, in far-off Aghaboe, County Laois, Canice was suddenly compelled to rush to the nearby church to pray for his friend, leaving in such haste that he lost a shoe. As he prayed, the storm abated and all aboard were saved.

Steeped in the Mists of Time

In the year 1170, the Lord of Leinster, Diarmard MacMurrough, invited the Earl of Pembroke (known as ‘Strongbow’) to Ireland to advise him on how best to keep his enemies in check. The Earl quickly fell under the thrall of the country, as would many other Normans. They became obsessed with building towns packed with impressive buildings, which signified their intention to remain permanently. They took to building a lofty cathedral at one end of their towns and a mighty castle at the other. This was the blueprint followed here, where a great castle was built that dominated the ‘High Town’, while at the far end the beautiful Cathedral was constructed.

Construction

There are no existing records that detail the construction of the cathedral, though it is thought that it was a two-stage process. A note from the sixteenth century indicates that the ‘first founder’ was the thirteenth-century luminary Bishop Hugh de Mapilton, who most likely built the crossing tower, transepts and choir. It is believed that the nave was the work of his near contemporary, Bishop Geoffrey de St Leger.

Dame Alice

In the year 1332, disaster struck when the central tower collapsed, an event inextricably linked with the infamous witchcraft trial where a newly arrived English bishop, Bishop Legrede, strove to have Dame Kyteler, her son and her maid Petronella tried for this heinous crime. While both Alice and Petronella were condemned to death, only poor Petronella was eventually burned at the stake. Alice fled, and her son William was ordered to repair the church roof as part of his penance. Though he did so, it was thought that the too-heavy re-leading he carried out contributed to the collapse of the tower, which, built on a far grander scale in those days, toppled on to the side chapels and choir, causing significant damage. Tongues wagged furiously – had William made it too weighty on purpose?

The Return of the Bishop

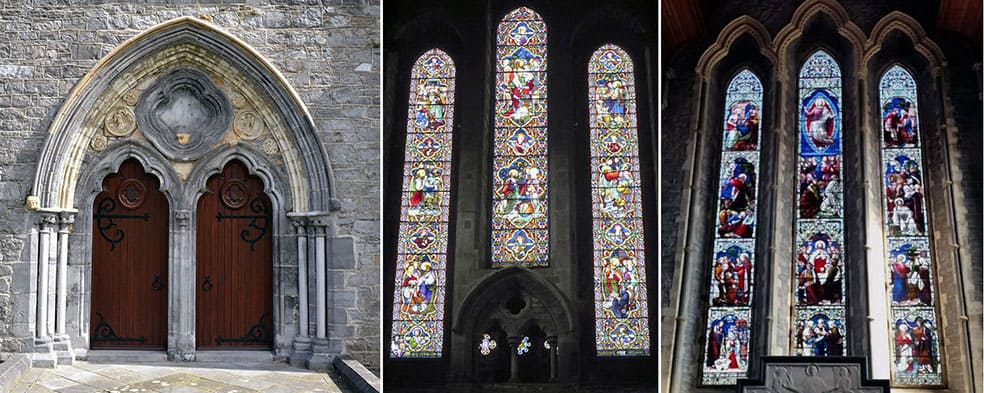

After all the controversy surrounding the Kyteler case, the bishop, well aware that he had fallen out of favour with both the king and the archbishop, had circumspectly taken himself off to the safety of the Papal Court, where he remained for the next twenty years. When he eventually returned, it was to a very different town – one that had been devastated by the Black Death. Still, the Bishop opted to carry out many repairs and improvements to his beloved cathedral, embellishing it with an astonishingly impressive stained glass East Window that depicted various scenes from Christ’s life. He also made the tower piers bigger, reduced the size of the tower and shored up a number of the supporting arches. Late in the fifteenth century, supportive vaulting was installed below the tower.

English Civil War

Cromwell captured the city during his ruthless campaign against Ireland, and in 1650 he and his men inflicted terrible damage on the cathedral. It stood roofless and abandoned for the next twelve years.

Renovations

Once the monarchy had been restored in 1660, it fell to one Bishop Williams to try to restore the building to its former glory, including re-roofing it. Later, in the 1750s, the repair mantle fell on the shoulders of the classically influenced Bishop Pococke, but by the 1840s the cathedral had yet again fallen into a sorry state.

Charles Vignoles

The current state of this glorious cathedral is due in large part to the efforts of Charles Vignoles. When he arrived in the 1840s as a Dean of the Cathedral, he was met by a building in a terrible state of repair and with jarring historical styles. Vignoles favoured the newly popular Gothic style, and he immediately set to work to restore the building, a process that was not without controversy. He found himself at odds with his incumbent bishop, Bishop O’Brien, and was forced to flee to France for a spell. However, on his return seven years later, he wasted no time in starting the restoration process that altered the cathedral into its present form. A great deal of the work was carried out by a local architect, Richard Langrishe. Their ambitious plans were finally achieved in 1900, when the choir stalls were installed. Sadly, Vignoles did not live to see his vision unveiled.

Gothic Glory

The cathedral benefited greatly from the talents of Vignoles and Langrishe. Their sensitive approach to the Gothic style prevented it from becoming overshadowed by its embellishments; instead, the revised design remained loyal to its medieval roots.

Key Features

Windows and Doors

The three beautiful sets of triple windows situated in the east end of the cathedral manage to be at once both elegantly simple and highly effective. The windows at the side have round heads – a fact worth highlighting, because Gothic style dictated that windows should have pointed ones. This could be an indication that this particular part of the building dates back to pre-Norman times; conversely, it could just have been a matter of proportion. The carved Romanesque door at the west end of the cathedral is particularly stunning.

Tombstones

The cathedral is packed with innumerable tombstones, and there are several that date from the early fifteenth century and merit a special mention. A common theme in those days was the symbols of the passion, which could be represented in a myriad of ways. One notable tomb is decorated with a carving of a cockerel sitting on a pot. According to ancient legend, on the day of Jesus’ crucifixion, a bird being boiled for Judas’s dinner rose from the cooking pot and crowed. Judas, realising that the bird was foretelling the resurrection of Christ, immediately returned the 30 traitorous pieces of silver he had received to betray his friend and hanged himself.

High Society

Many of the tombs contain the remains of wealthy and powerful former residents of the city, with their status indicated by the fact that males are seen in full armour with their loyal dogs at their feet. Female tombs are decorated with elaborate examples of medieval dress.

Craftsmen at Rest

Located nearby are three tombs containing craftsmen – each trade is carefully carved: cobbler, carpenter and weaver. During the Civil War, many of the tombs were defaced or overturned by Cromwell’s men, and though they were re-set in the nineteenth century, most of them are no longer in their original positions.

Barack Obama

One tomb has a fascinating link with the present day. Bishop John Kearney (who died in 1813 and whose remains were entombed at the west end of the cathedral) is a distant relative (great-great-great grand uncle) of no less a figure than American President Barack Obama.

Alice’s Father

Another honourable mention must surely go to a highly polished grave marker located along the northern wall. Here is found a slab that is marked with the name ‘Jose de Keteller’, who died in the year 1280. It seems highly likely, despite the alternative spelling, that this is indeed the tomb of the father of the ‘witch’ Alice Kyteler.

St Kieran’s Chair

Visitors should also look out for the impressive stone chair of St Kieran, which sits embedded into the wall itself. Dating from the thirteenth century, it is said that the stone that lies beneath the seat itself was once part of the first bishop’s throne in Aghaboe (c. the year 400), though the sides date from the erection of the cathedral itself.

The Bishop

One the most prominent tombs on the site of St. Canice’s Cathedral and the Round Tower in Kilkenny belongs to our old friend Bishop Legrede – his name forever associated with Alice Kyteler and her doomed maid Petronella.

Visiting St. Canice’s Cathedral

St. Canice’s Cathedral, Kilkenny, is open all year round, although times vary according to the season. It is recommended that you arrive at least half an hour before closing to avoid being refused entry. Combination tickets are available – these cover entrance to the cathedral and the Round Tower. Please call ahead to arrange these for larger groups. Family tickets are also offered. Information leaflets written in 15 different languages are available as is a gift shop and toilets. Please note: Under-twelves are not permitted to climb the Tower, and access is dependent on the weather. There is not currently any parking at the cathedral. On-street parking is available on Dean Street, and there are a number of car parks in Kilkenny city centre. There is one disabled parking bay outside the cathedral gates on Coach Road.

Admission prices & opening times:

Adult: €4.00; Senior/Group & Child/Student: €3.00; Family: €12.00.

October – March:

Monday to Saturday: 10am – 1pm & 2pm – 4pm. Sunday: 2pm – 4pm

(Please note: The Round Tower opens Monday to Saturday 12noon to 3pm between October and March)

April, May & September:

Monday to Saturday: 10am – 1pm & 2pm – 5pm. Sunday: 2pm – 5pm

June, July & August:

Monday to Saturday: 9am – 6pm. Sunday: 2pm – 6pm