St Michan’s Church, Dublin has existed in one form or another for close to a thousand years, from where it has borne witness to centuries of Christian traditions and a history that includes influential figures such as the composer Handel. The Mummies that lie in its crypt are a major attraction today, but there is so much more to this church’s history than its most famous inhabitants.

History of St Michan’s Church, Dublin

Located on a site dating to Hiberno-Norse times, and bordered by an ancient forest of oak and the River Liffey, the original St Michan’s Church was built in a position set some distance away from the fortified castle and city.

It was built with the purpose of serving the religious needs of a group of Vikings who had been banished from the city, and for over five hundred years it was the only parish on the north side of the river.

The first church on the site was constructed from wood by the members of the Oxmanstown Danish colony in 1095 and was officially consecrated the following year (though strangely, one of the mummies interred in the crypt dates from the middle ages).

It is not entirely clear from where the church took its name, though there was a Danish bishop with the name Michan. Another theory links the name with an Irish confessor and martyr. In 1541, St. Michan’s was placed under the control of Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral by Henry VIII, and in 1544 the two were permanently linked.

John Parker, senior clergyman at the church in 1643, was imprisoned by Cromwell and fled to England upon his release. In his absence, his position was filled by a Commonwealth minister, Daniel Neylan, who ran the church according to puritanical theology. This meant no holy sacraments – indeed, the font was removed from the church entirely – and the pews were reconfigured to the newly centralised pulpit.

After the Restoration, Parker returned to Ireland and was eventually appointed Archbishop of Dublin in 1679. During the latter half of the seventeenth century, an increase in the city’s population inevitably led to a growing demand for good-quality land, as many of the more affluent inhabitants started to move beyond the traditional city limits.

Anticipating this development, Dublin’s then mayor, Sir Humphrey Jervis, planned out a new residential area to the north of the river Liffey. As a result of this, two brand new parishes were established in 1686 – St. Mary’s and St. Paul’s. The present structure of St Michan’s dates from around 1685, when a major programme of church re-design and re-building was undertaken which resulted in a neo-Renaissance-style structure – a design that reflected the new, rather more upwardly mobile congregation.

Further renovations took place between 1723 and 1725, in 1767 and in 1825, when the church was closed for three years while the interior was given a facelift.

Incidentally, the church organ is one of the oldest still in use in Ireland. The original was built by John Baptiste Cuvillie during the renovations of 1723-1725, and though it was later rebuilt, the original eighteenth century casing remains. It is thought that George F. Handel played it while he was composing (or at the least revising) his most famous work – The Messiah.

Mysterious Inhabitants

Despite the care lavished upon it, by the nineteenth century the church was experiencing a declining congregation, due in no small part to the fact that the city’s population was slowly but steadily moving southwards.

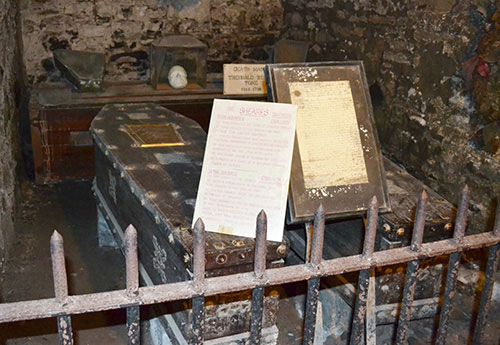

However, as the twentieth century loomed, so St. Michan’s began to see an influx of tourists keen to visit what remains the church’s main claim to fame, which actually lies beneath the church. If you are brave enough to go down the stone stairs, you will discover a sizeable vaulted space complete with long galleries and chambers on each side. Some of the vaults are private, which is indicated by portcullis-style gates or iron doors, while others are open. Peer through the bars blocking certain of the vaults, and you will see caskets containing the eerily well-preserved remains of corpses dating as far back as the seventeenth century.

Over time, as the church building evolved and was modernised, the vaults beneath it were left unchanged, allowing the mummification process to continue unhindered. Various theories have been posited as to why the copses are so unusually well preserved, and questions raised as to why the corpses seem largely impervious to the ravages of time while their coffins disintegrate around them. The limestone walls and parched atmosphere seem to have created an environment ideal to maintain its ancient residents’ shrivelled skin mostly intact.

In one of vaults towards the back of the crypt lie three parallel caskets. On the right is ‘the unknown’ – a female; in the middle there is a male – ‘the thief’, who is missing both feet and a hand; and on the left are the remains of a ‘nun’. Behind, set apart along the rear wall, lies the coffin that holds the eight hundred-year-old remains of a soldier known as the ‘Crusader’. Standing at 6½ feet tall, the ‘Crusader’ would have been regarded as a near giant during his lifetime, and it seems that those who laid him to rest had to break his legs in order to fit him into his casket. How the corpse of a soldier from the Middle Ages ended up in a church that was not consecrated until 1685 is an enduring mystery.

Notable Figures

Also entombed in the crypt of St Michan’s Church, which is often associated with Bram Stoker, are the remains of many of the city’s most influential seventeenth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century families, including the beautifully decorated caskets of the various Earls of Leitrim and the bodies of brothers Henry and John Sheares. Members of the Society of United Irishmen (a society that was banned as a result of the climate of fear inspired by the revolutionary unrest in France and that country’s declaration of war on Britain), the brothers were accused of being traitors for their part in the 1798 United Irishmen Rebellion.

They were arrested and subsequently executed on Bastille Day that same year by the traditional and barbaric method of being hanged, drawn and quartered. Today a plaque bearing the United Irishmen symbol – a harp – marks their burial place. Other notable mummies in situ here include the mathematician William Rowan Hamilton and (allegedly) the legendary Irish rebel Robert Emmet, who was killed in 1803 by the British.

Fascinating Facts

It is thought that Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula was inspired by the author’s childhood fascination with the mummies in the crypt (he became aware of these during visits to the family burial plot in the regular graveyard).

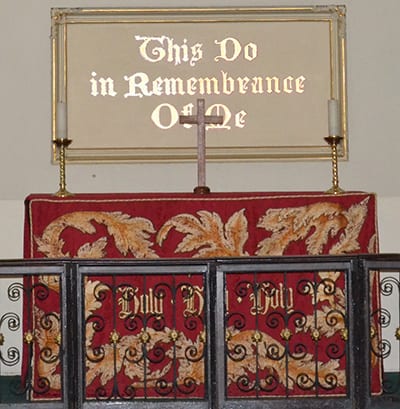

Indeed, the name ‘Dracula’ comes from the Irish ‘droch-fhola’, which translates as ‘bad blood’. A final absorbing fact about St Michan’s Church is that its eye-catching red altar cover adorned the altar at the Royal Chapel within Dublin Castle until 1922, when it mysteriously went missing. It was found in a flea market and was lovingly restored and installed in St. Michan’s.